Originally published by R.C. Barajas in the Washington Post Magazine: Sunday, March 28, 2004

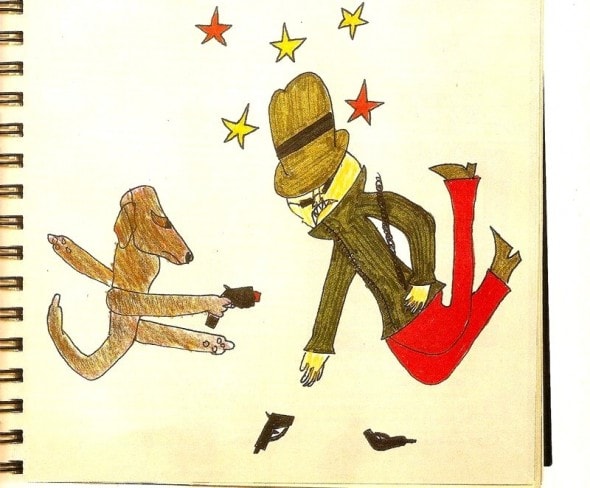

Published with several drawings by Sebastian Barajas. Above is one example.

My three boys shrugged on their coats.

“We won’t find anything,” muttered Sebastian, the oldest, as he climbed into the car. “They’re always too big, or too hairy, or something,” We had been to two dog adoption events without finding a dog that suited us, and the boys were already discouraged. But for some reason I had a feeling this would be the day.

Sebastian, Julian, Gabriel and I drove to the Baileys Crossroads Petco, where the Lost Dog and Cat Rescue Foundation (LDCRF) exhibited its available dogs. On the sidewalk in front of the store, a bruiser named Rocky appealed to us, and a volunteer encouraged us to take him for a walk. The dog was a slobbery, muscular charmer, the product of big-chested, wide-mouthed forebears, with powerful jaws that could have snapped a chair leg. His mismatched eyes rolled at us, and we joked about naming him Mad-Eye. But once he was on the leash, the nylon fibers stretching to the breaking point, it became clear that Rocky was too much dog. The twins, 9 and not particularly tall for their age, had to throw their arms across their faces to fend off his giant tongue, and Sebastian, wiping his sodden sleeve on his jeans, shook his head.

“He’s sweet and everything,” he said, “but he’s just too hyper.” Sebastian would be entering middle school soon, and was tight-lipped about his feelings concerning the unknown demands ahead. But finding just the right dog — a dog that would be loyal to him, whatever challenges he might face at the new school — seemed to have taken on tremendous importance to him.

We wandered inside where we spotted a young dog, puppyish in her proportions. When the boys patted her, she offered up a few licks as their hands bumped over her ribs. Her papers said she was a 6-month-old hound mix, but she looked closer to a year. Her file said her name was Kelsey, and that she had been rescued by LDCRF from the Spotsylvania Animal Shelter, where she had been brought in by her owner. “Can’t keep her no more,” was all the person had managed on the give-up form, along with ticking the “yes” box next to good with children.

We walked her outside, through the rush of eager, adoptable dogs and across the street, noticing a samba-like sway in her hindquarters. I could see that under the dense brindled coat, she needed fleshing out. She accepted a treat or two, wagged her tail — which, judging by its various unnatural angles, had been broken in several places — and exhibited a slight favoring of her left hind leg. But her shy, waiflike beauty and her gentleness were captivating. We all looked at one another, grinning, and then went inside to fill out the adoption papers.

After contemplating a dog for so long, and then after many months of reading the want ads and searching the Internet, it was a strange feeling watching this unfamiliar creature, this shedding, limping hound dog, hop gingerly into our car for the first time. The boys clambered in behind, giddy but a little uncertain.

“I get to sit next to her!”

“No, I do! Why is it always you?”

“Go ahead. I don’t want to — she stinks.”

At home, Mocha — as we finally renamed her, for the chocolaty colors in her fur — was sweet but withdrawn. She curled up in her bed and stayed there for two days. At her first vet visit that week, she and I were both nervous. Steven Rogers of the Falls Church Animal Hospital thought she looked thin, and was concerned that there was something abnormal in her leg or hips.

“She’s got a strange rear end,” he said. “Could be a badly healed pelvic fracture from a car accident, or an ACL [anterior cruciate ligament] tear.” He put her on a slew of medications for infections and parasites, and said if her limp didn’t clear up in a few weeks we should get X-rays.

Her limp didn’t go away, and we returned. Dr. Rogers strode into the examination room where the boys and I were waiting. “Well, it’s not her hips, and it’s not her ACL,” he said, with grim certainty. He snapped the X-ray into the light and pointed to two fuzzy ovals surrounded by what looked like gray dust. “Those are bullet fragments.”

It seemed that we stopped breathing. Six weeks had been more than enough time to bind these boys to Mocha for a lifetime, and the thought of a bullet ripping into her leg produced a sputtering explosion of outrage, condensed to a question aimed at the world in general and the vet in particular:

“What kind of person would shoot a puppy?”

Dr. Rogers just shook his head. He had clearly seen this kind of thing before.

After that, the boys looked at Mocha differently — reverentially — and the favorite topic at the dinner table for many days became what each of them might do if they found the unspeakable lowlife who’d shot her.

Over the next few weeks, it became clear that Mocha was a fearful dog. We could see that now. Tall men especially terrified her when they came to the house, and she would bark menacingly. She wasn’t aggressive, but I was concerned that her fear could make her dangerous. Although small and slight, she could look vicious. I paid for group obedience classes, which turned out to be of little use because she was terrified of the trainer. When my parents came to visit that April, she kept up a steady, suspicious growl at my father. Back home, they told my sister about the unbalanced dog I’d gotten mixed up with. My dad said, “She’ll have to be gotten rid of,” my sister later confessed to me. I almost despaired, and had guilty daydreams of never having gotten Mocha — or worse, of returning her.

But what kept my faith in her was her ease and obvious pleasure around children. In their presence, her tail would wag, she would sniff them all over and follow them happily, like a protective nanny. As she accepted our home as her own, she adopted the boys as her charges and playmates. She came to know exactly when the school bus would arrive, and would scratch at the front door at 3:45, going to where I keep her leash, and looking at me expectantly. We’d walk to the bus stop, and when the bus arrived, she’d wag herself to pieces as the boys tumbled off and wrapped their arms around her neck. But I knew she needed help, and so I decided to get her some one-on-one training.

We had 11 sessions with Michelle Beardsley, who owns a business called Capital Canines. Beardsley trains dogs and their owners, focusing on obedience, behavior problems, and even agility training. It was Beardsley who recognized that Mocha had been poorly socialized — meaning that in her formative months she didn’t have enough interaction with dogs or people, making her uncertain and nervous. Beardsley also pointed out that Mocha was a dog’s dog — more comfortable with other dogs than with people.

“She’s what I’d call primitive,” Beardsley said one day, as she watched Mocha practicing her sit-stay. “It could just be the way she was born, or maybe she’s had to rely on her wilder canine heritage to survive.” In fact, Mocha had all sorts of rituals that could be called primitive, like routinely dashing from the kitchen with a mouthful of kibble to “bury” in the carpet — saving for lean times, I guessed. She even tried to hide chew toys in the floor of the twins’ room, whimpering when she encountered, for the hundredth time, the obstinate hardwood. She shied away from open hands and barked and growled at strangers. She was primitive, certainly. At some point that might have been what saved her.

Beardsley’s training left Mocha and me deeply bonded. I got comfortable being in charge, and Mocha began to see that trust would now be rewarded — with treats, with a soft bed by the heater, with three boys competing for her affections. But the mystery of Mocha’s earlier experiences still haunted us. We would watch her and wonder aloud what had happened, what her life had been like before. And we continued to speculate on who had shot her.

Sixth grade was soon in full swing for Sebastian, with its many social and academic demands. Perhaps in response to these, Sebastian, who had always enjoyed drawing, soon began a new sketchbook and started drawing in it every free moment he could find. In page after page, he began to explore and document Mocha’s story as he envisioned it, conjuring from his pens an intriguing alter ego for her.

In Sebastian’s serialized version of Mocha’s life, she does what he cannot — she searches for revenge against the shooter. His comics show not the scared, innocent puppy she was, but a cunning and merciless warrior, no longer defenseless but armed to the teeth with weaponry and kung fu moves. She speaks in her own unique vocabulary, such as, “Eat my laser, and my ill wishes!” and, “Oh, you cliche weirdos!” Against the thugs she meets, she “does the Matrix,” leaping high in slow motion, twisting and firing. Perhaps Sebastian is living through her, enjoying her ability to defeat her enemies with such composure and finality. Friends and neighbors come regularly to see the latest installments of what have become known as the Mocha Comics. He reads them aloud, using different voices for all the characters, as his listeners turn and look with amazement at the sleeping dog that inspires them.

Lately, Sebastian’s drawings have begun to reflect Mocha’s growing contentment and peace with the world. She now relaxes in a hot tub — a fountain in the background flows over rocks and around bonsai, while next to her a record player spins out music, and a towel with her name awaits. Mocha is taking a break from action-packed vendettas, happy to live the dog’s life, as it were, though Sebastian is adamant she has not retired. He, too, seems to be having an easier time of things. His comics currently feature himself and his friends as the main characters, facing nothing more dangerous than an overly zealous teacher, or a schoolyard bully.

But Mocha cannot abandon her old life completely. Her next adversary, Sebastian has decided, will be an abused dog, trained to be fiercely aggressive. “I find metaphors for real life really tiresome,” says Sebastian, though he admits that this new, ferocious villain is symbolic of the very fate his beloved dog escaped. “Mocha was a hair’s breadth from going in the same direction, you know.”

Come back tomorrow night for the second installment!

For more information on R.C. Barajas, please visit her website.